Whilst the country consumes itself with the consequences of a ‘No Deal’ Brexit, EU negotiations and trade deals, our new report reveals the devastating impact this preoccupation has had on children’s lives in England, leaving many traumatised, powerless and vulnerable to abuse in many areas of their lives.

30 years after the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) was first adopted by the United Nations, our annual State of Children’s Rights in England report takes a look back at the past year to assess how well the government is respecting children’s rights. The UK signed up to the UNCRC in 1991. This means that all areas of government and public institutions, including local government, schools, health services, and criminal justice bodies, must do all they can to fulfil children’s rights. The UNCRC sets out the basic things that children need to thrive and have a good childhood but also acts as a safety net so children always receive at least the minimum standard of treatment.

Sadly, evidence from our 100 members (made up of the leading children’s charities and academics) and new data shows the government has made little progress on important issues such as child homelessness, rising school exclusions and how children are treated by the police; ignoring stark warnings from the UN. The wellbeing of the nation’s children should be one of the government’s top priorities, yet we have found clear evidence that children’s best interests are being overlooked and their rights violated because of a focus on Brexit and systematic failures to protect them.

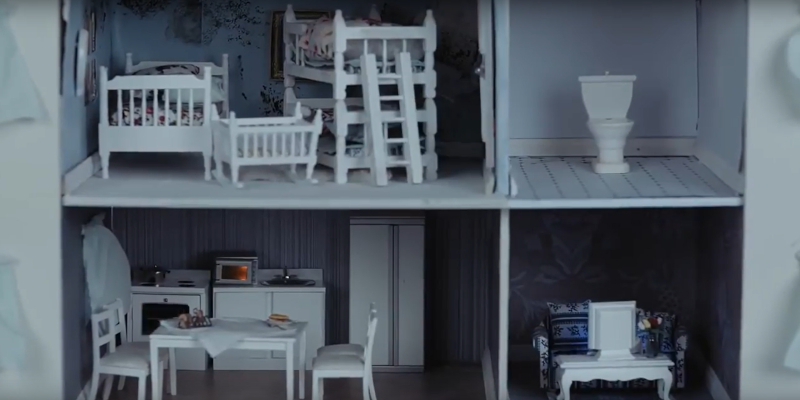

Despite repeated recommendations from the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, our FOI (Freedom of Information) requests have exposed that local authorities are using a legal loophole to house families in B&B accommodation for longer than the legal limit. A shocking 1,641 families with children were housed in council-owned B&Bs and hotel-style accommodation in 2017, almost two thirds (1,056) for longer than 6 weeks (the maximum time councils are allowed to house families in privately-owned B&Bs). This can put children at great risk as they are forced to live alongside adults with drug or alcohol problems and have no safe space to play or do homework. As one child told us: “You’d always see people smoking joints and other stuff, and loads of alcoholics sitting about. I never felt safe there.” (Carl, 16)

We found increasing numbers of children, including those in care, housed in independent accommodation such as B&Bs, hostels, and even tents and caravan parks, many of them for long periods. At least 1,173 children were housed in independent accommodation for longer than 6 months in 2017, including 19 children aged as young as 15 and one aged 14. Such accommodation is often unsupervised and leaves already vulnerable children at risk of further exploitation and abuse.

Our research also found that police use of force on children is on the rise, disproportionally affecting children from Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) backgrounds. Our FOIs discovered police use of Tasers against children is increasing, with 871 uses in 2017 and 839 in just the first 9 months of 2018. Shockingly, Tasers are even being used on children as young as 12 and on 4 occasions on children under 10. BAME children accounted for 51% of Taser use. This was a staggering 68% for the Metropolitan Police Service.

The use of spit-hoods - mesh bags placed over the head - on children is also increasing year-on-year as more police forces roll out their use and increase the number of instances in which they can be used. This is despite risk assessments by the police highlighting the dangers of ‘breathing restriction and asphyxia’ and the Independent Office of Police Conduct investigating the deaths of several adults following the use of spit-hoods.

Shockingly, we found spit-hoods used on children as young as 10, with at least 47 uses on children in 2017 and 114 incidents in the first nine months of 2018, although the true figure is likely to be much higher. BAME children accounted for 34% of spit-hood use nationally and again disproportionate use on BAME children was much higher by the MPS at 72%.

While the report also highlights positive examples of government action to improve children’s rights, such as steps taken to better safeguard children in care and those with mental health issues, we still have a long way to go to achieve the positive vision of childhood set out in the UNCRC back in 1989. The government must use State of Children’s Rights to identify and take key actions to make this a reality for all children before it is next examined by the UN Committee in 2021 and before children’s lives are damaged further.

Louise King is Director of the Children's Rights Alliance for England, and Director of Policy and Campaigns at Just for Kids Law. The State of Children's Rights in England 2018 report is published today.

This article was first published by openDemocracy. It was published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence and is republished under these terms.